Rickshaw or a shift for the better

Rickshaw painting in Bangladesh are fascinating, unfortunately a potential creative industry is dying. Rickshaws are to Dhaka, what jeepneys are to Manila and tuk-tuks are to Bangkok—unconventional forms of public transport that add colour and a particular outdated flavour to the city's traffic. The rickshaws are manually driven, slow-moving, lightweight, environment-friendly, economical and romantic vehicles that look more like medieval contraptions than modern-day transport. You hardly need to walk in Bangladesh. Once you reach a street, a rickshaw or several will appear, with little bells tinkling to get your attention. Once your destination and fare are settled, the puller steps up from the seat, brings all his weight to bear on the paddles, and begins the journey.

Once upon a time, Rickshaw Art or painting used to be a huge industry in Bangladesh, which has lost the battle with modern technology.

The origin of the Rickshaw invention and the name of the inventor remains uncertain. One source indicates that an American missionary to Japan, Jonathan Scobie, invented the rickshaw around 1869 in Yokohama. Another source says the Jinrickshaw originated in Japan in the 1870s, but in the 19th century, it was first introduced and used in Japan as a similar form to the old French brouette.

The three-wheeled rickshaws first appeared in Dhaka around the late 1930s. According to an account, they were introduced by a local landlord (Zamindar) and a businessman. Even today, these have remained a major and convenient form of transportation for the millions of citizens of Dhaka and all other cities and villages of Bangladesh. Thus, while rickshaws have disappeared from all big cities, they have continued to flourish here.

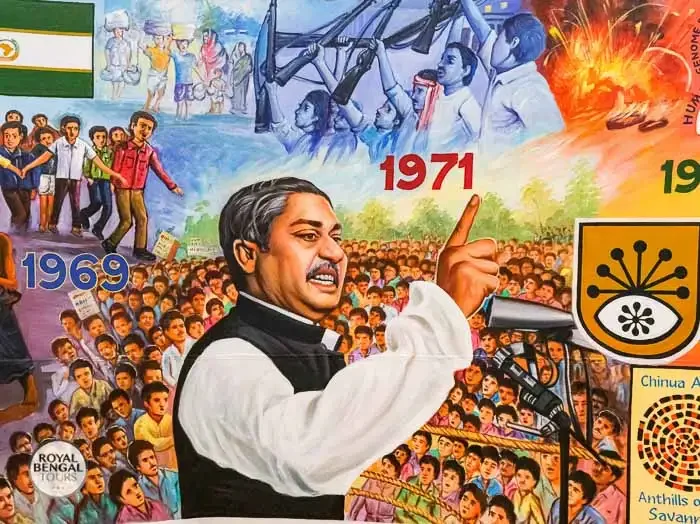

Till the early eighties, rickshaws were the common mode of transportation in Dhaka. Even today, this economical, non-polluting form of transport is a way of life for millions of people: the men or women who ply rickshaws, and those who make, repair, or decorate them, as well as those who ride on them. Often Rickshaws remains the only form of inexpensive transportation during heavy monsoon rains or partial flooding on Dhaka streets. Embellished rickshaws have been called “moving masterpieces”. Their colourful backplates reflect both male desire as they do contemporary politics and serve as a useful barometer to gauge the mood of the people. Today, however, the rickshaw is viewed as a traffic hazard and is being increasingly threatened by rapid urbanization and mechanization. There are about a million rickshaws playing on the streets of Dhaka metropolitan city to commute people and goods for a shorter distance.

Rickshaw pullers are usually rural migrants. With no other jobs due to many reasons: e.g., monsoon water covered the seasonal agricultural lands, he has no land on his own or no opportunity of daily basis labour jobs and so on; they turn to a rickshaw garage owner (called a malik) in the nearby city. The driver completes some registration process using his National Identity card or by a strong reference of a known person to be able to hire a rickshaw with a daily basis rental system. The malik rents out a rickshaw from his garage and usually also provides meals and basic dormitory-style accommodation with a small fee.

The maliks commission rickshaw makers called mistris to build and decorate the machines to their specification. The artists working in the mistri’s workshop learn on the job from a younger age, when they work decorating the upholstery and smaller sections of the rickshaw.

Art moving by on wheels are bold and eye-catching

Rickshaw art: the moving picture galleries

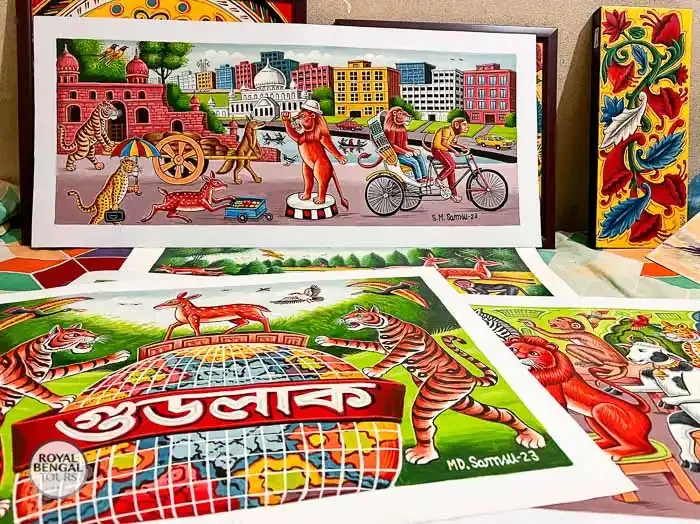

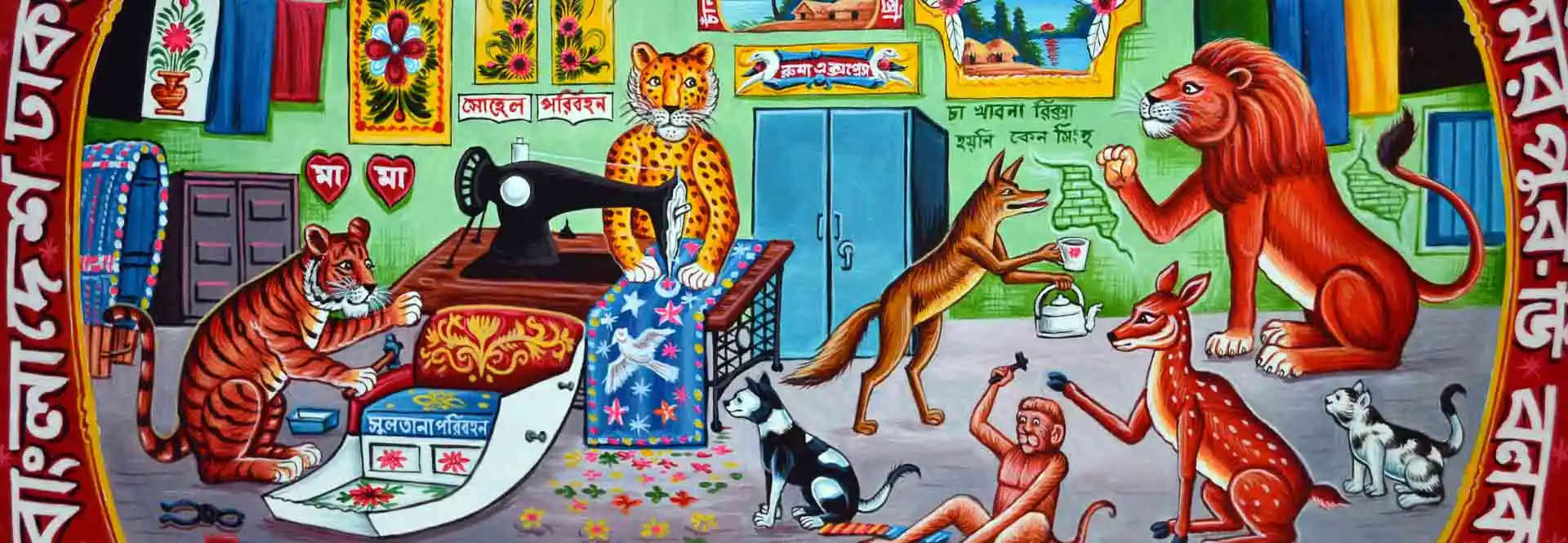

Rickshaw artists aim to decorate the vehicles with as much drama and colour as possible and paint images that are both memorable and simple. This is street art for ordinary people, and it is unashamedly commercial. Rickshaw painters compete to win deals from the rickshaw fleet owners, who in turn compete among themselves to own the fanciest vehicles.

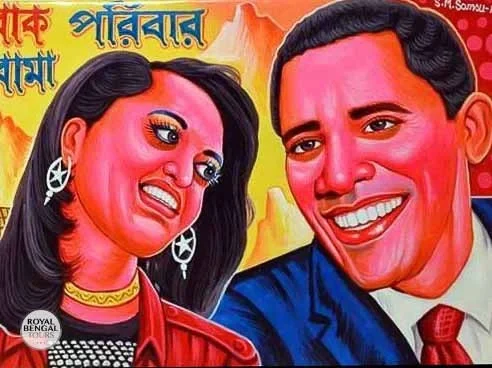

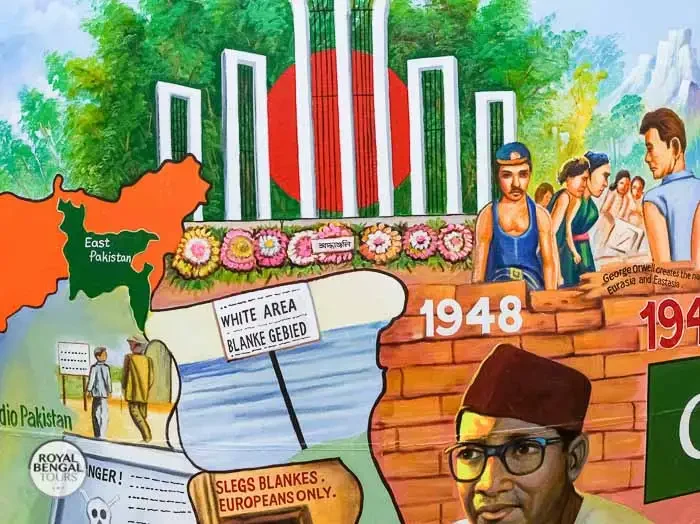

People have been charmed by the sixty-year-old art form associated with rickshaws, more formally known as rickshaw art or rickshaw painting. Like transport painting elsewhere in the world, rickshaw painting in Dhaka has assumed an identity and a charm on its own. Variously described as “naive”, “commercial”, or urban-folk” art, rickshaw art has developed steadily since the 1950s, undergoing transformations as its scope expanded. While the entire rickshaw usually has floral decoration, the backplate contains the main artwork. The themes depicted therein have changed over time, reflecting changing social realities and shifts in public taste. At first, the main subjects consisted of the romanticized image of popular film heroes and heroines. Over the years, though, rickshaw painting has taken as its subject a wide range of themes and images: village landscapes, real-life events such as the liberation war of 1971, fantastic looking gardens that appear right out of some J.R.R Tolkein book, postmodernist cities, animals and birds, public monuments, mythic and fairy tale figures, airliners, and cruise ships and religious or devotional icons and images.

The main ‘canvas’ is recycled enamel painted tin collected from a drum of cooking oil, for example. This forms the lower backboard, which is the most visible paint area and the heart of rickshaw art. This rectangular piece of tin plate is not bigger than 45cm X 25cm in size and secured between the two back wheels, some way above the ground, and is clearly seen even from a distance. Rickshaw is heavily painted over in rich, profuse designs and patterns, the seat cover and the collapsible hood, usually made of bamboo, rexine cloth and plastic, are profusely painted. Applique work is often done on the hood and the upper back part of the body. The artist also decorates the seat, the curved back of the seat, handlebars, the chassis and just about every other surface. Therefore, every rickshaw is a moving picture gallery.

Unfortunately, the economy of mass production and consumerism has finally arrived, posing a major threat to the sixty-year-old tradition of rickshaw art. Only 10-15 per cent of the rickshaws today display old-fashioned, hand-painted art. Rickshaw painting is certainly not a sophisticated form of art, but neither is it a naive display of artistic inclinations. It is a public form of art where a combination of factors plays an important role – the economic status of the painter, his particular taste and training, the taste of the clients, the public preference for particular images at a particular time, etc. Rickshaw art is a folk art of a kind that thrives on particular myths, symbols and icons, with distinctive urban colouring. We may call this a form of urban folk art, with a considerable portion of popular art elements thrown in. But whatever label we may give to rickshaw painting, one thing is certain: we will have this art form with us only for a decade or two more. Which thought makes one wonder: how many art forms are there in the history of art that has encapsulated the popular imagination so comprehensively and yet were unable to survive even for a hundred years?